Born Again Media Orleans New York

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference, often referred to as the SCLC, was one of the most significant participants in the civil rights motion in the 1950s and 1960s. The organization is still active on issues of social justice. Although it has been active and influential in other southern states, this national organization has always been based in Atlanta, and Georgia has been the home of many of its founders and leaders.

Origins

The SCLC had its origins in several mid-twentieth-century phenomena. Black veterans returning from service in Earth War 2 (1941-45) were no longer willing to take injustices at home that they had fought confronting abroad; Black southern churches were powerful social institutions; Black voters were becoming more involved in the Democratic Political party; and the Supreme Court's 1954 Brown v. Board of Education determination strengthened a national movement to desegregate public schools. African Americans began to join together in local political clubs and attract a broad base of supporters, amongst them many who felt that the National Clan for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was too radical.

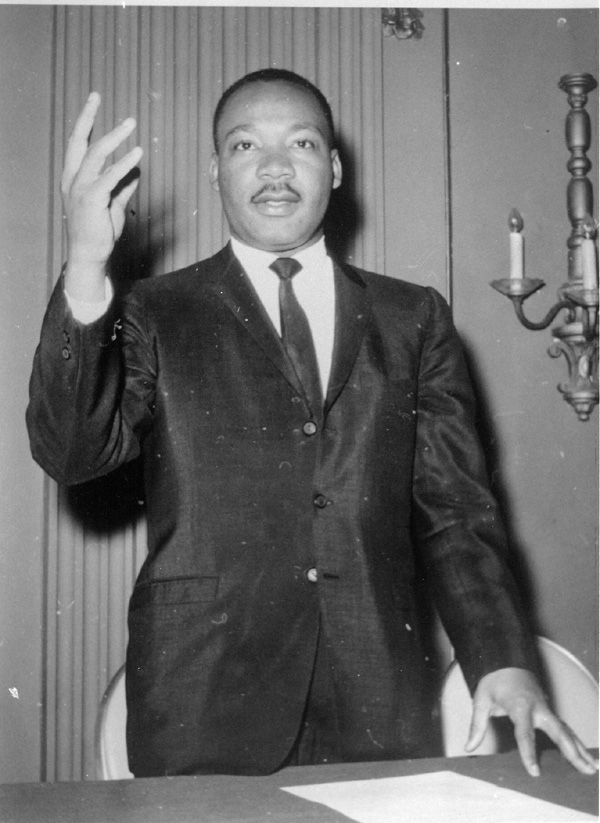

The event that triggered the formation of the SCLC was the Montgomery, Alabama, charabanc boycott in 1955-56. Although non begun past church leaders, the movement was before long joined by Montgomery's Black ministers, who kept the boycott alive and ensured its ultimate success. Georgia-built-in Martin Luther King Jr., then living in Montgomery and recognized for his courage, intellect, and leadership skills, was chosen as their spokesman. News of the boycott (and others in Birmingham, Alabama, and Tallahassee, Florida) was carried all year by the New York Times. As a upshot, influential northern pacifists of both races saw the opportunity to broaden the cold-shoulder movement into a southern civil rights move.

During a briefing at King's alma mater, Morehouse College in Atlanta, the formation of a ceremonious rights arrangement was discussed. Both southerners and northerners at the conference decided to keep its focus regional, to include "Christian" in its title to attract equally many church building leaders and lay people equally possible, and to establish its headquarters in Atlanta, where a large, financially secure middle-class Black population, including many graduates of the elite Blackness colleges there, could be chosen upon for support. The SCLC was officially inaugurated in Atlanta on January 10-11, 1957, and a follow-up meeting was held in New Orleans, Louisiana, several weeks subsequently, on February 14.

Early Years

From its beginnings the SCLC was an urban arrangement. Its early success in attracting members is attributed past many historians to King's abilities and prestige. Among other Georgians who were important in early on SCLC efforts were King's married woman, Coretta Scott King; Ralph David Abernathy; Joseph Lowery; and Andrew Young.

As its headquarters, Atlanta was naturally the focus of some of the earliest SCLC activity in Georgia. In many cases an action was started past another ceremonious rights organization (such as the Educatee Nonviolent Coordinating Commission or the Congress for Racial Equality), with Male monarch and other SCLC members joining in to help. At the asking of Atlanta Academy (later Clark Atlanta University) and Morehouse College students, King joined a sit-in on October nineteen, 1960, at the Magnolia Tea Room in Rich's Department Store in downtown Atlanta. He and a number of others were arrested and jailed on a recently passed police force against trespassing. This brought national attention beneficial to the civil rights cause.

The SCLC leadership considered training new political activists in nonviolent tactics a priority and opened a middle for that purpose in Liberty Canton, at the Dorchester Center, where they trained hundreds of volunteers within the next few years. It was in this centre that i of the nigh significant campaigns, the Birmingham, Alabama, demonstrations of 1963, was planned.

Efforts in Georgia

Notable Georgia actions involving the SCLC include form-action suits filed against government at all levels for maintaining segregated employee lunchrooms; sit-ins (and variations such as "wade-ins" and "kneel-ins"); rallies and marches held to desegregate public places;

In Dec 1961 a series of mass meetings and protestation marches known equally the Albany Movement for desegregation was held in Albany. Its leaders invited Male monarch and Abernathy to speak at the rally. Rex and Abernathy led most 264 people to the Albany City Hall only were arrested for parading without permits. Although the city agreed to some desegregation measures, information technology soon reneged on the understanding. In July 1962 King and Abernathy were convicted of leading the Dec march, and the SCLC renewed its protests.

Reprinted from Freedomways

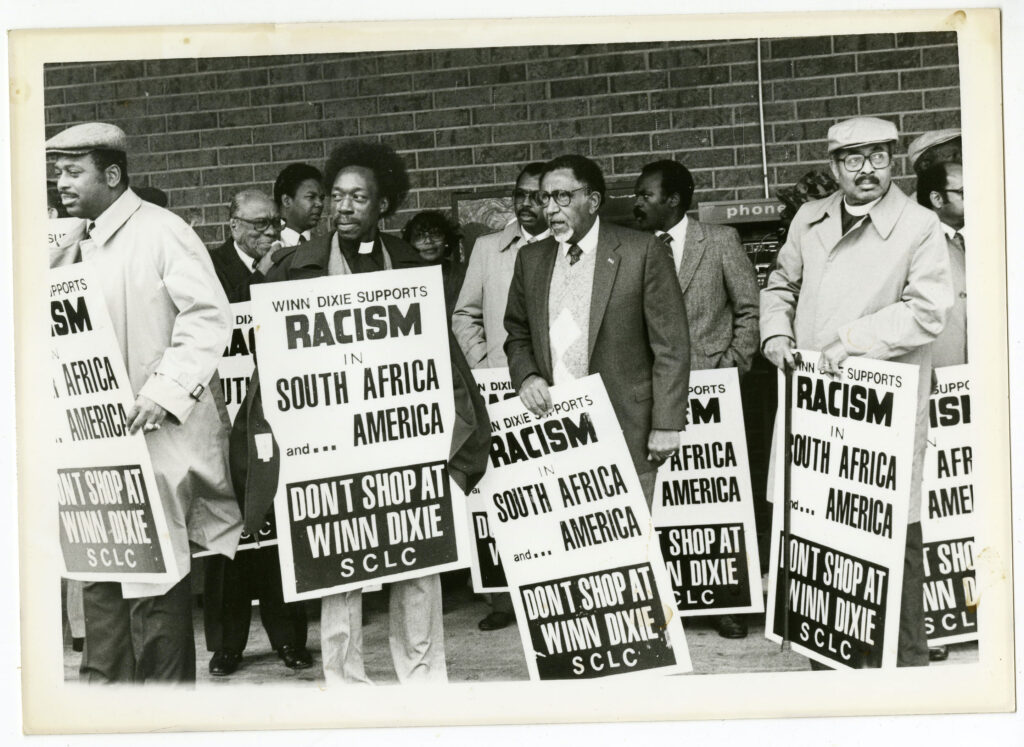

Likewise in 1962, Performance Breadbasket and the Citizenship Teaching Program were organized past the SCLC in Atlanta and spread throughout the South to elevate the economic status of African Americans past concentrating on the job market place, literacy programs, voter education, and customs organizing programs.

In June 1963 demonstrations were initiated in Savannah by Hosea Williams of the Chatham Canton Crusade for Voters. Joined by thousands of people, many of them SCLC members, the demonstrations eventually turned violent. The SCLC, wishing to reach its goals nonviolently, chosen for their end. The rallies, sparked by the refusal of some Savannah picture show theaters to desegregate, led to a more general integration agreement won by Baronial 12.

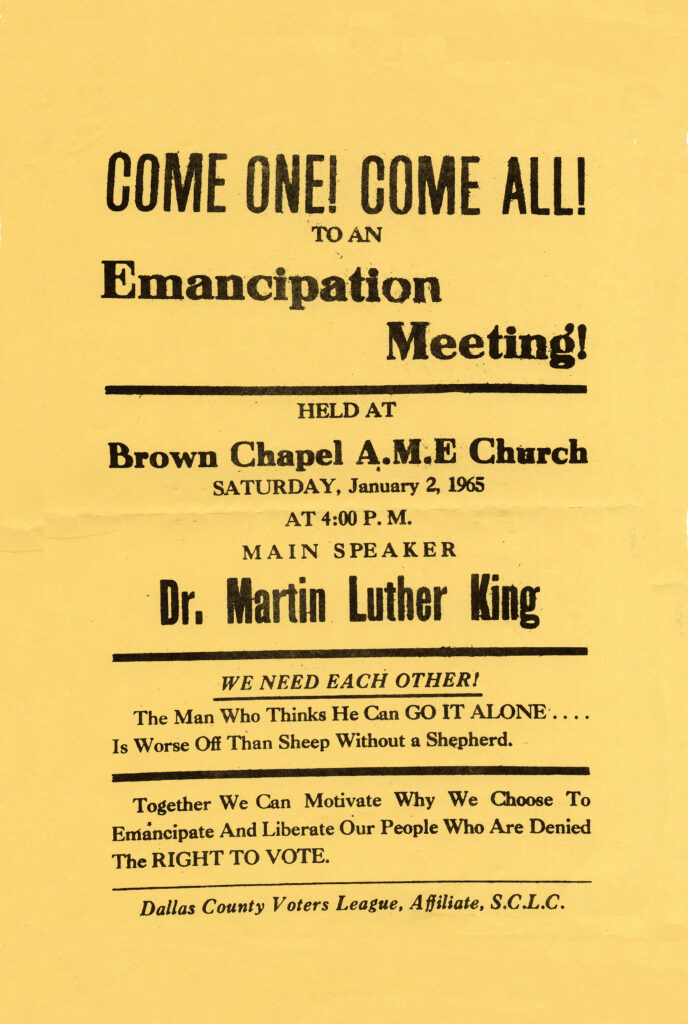

On October 22, 1965, SCLC "right-to-vote" marchers in Lincolnton were attacked and beaten. The next year, however, an SCLC voter registration drive in Hancock Canton, which had ane of the state'due south highest concentrations of rural African Americans, led to the enfranchisement of peachy numbers, who by their votes and courage (and against previously insurmountable barriers) changed their own lives radically over the next two decades.

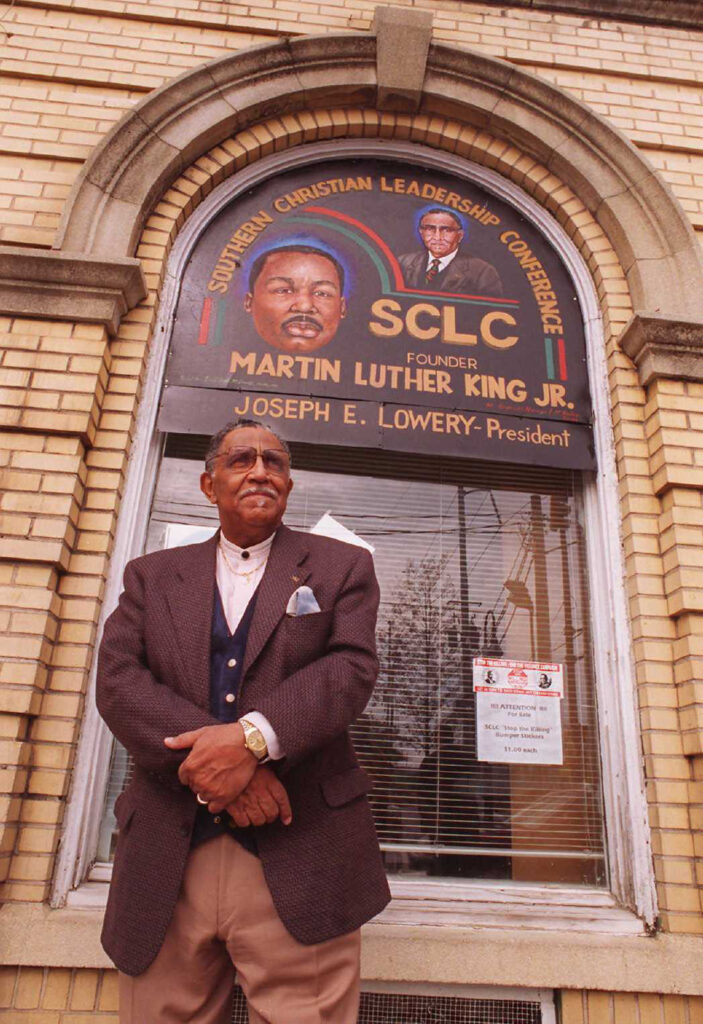

In 1978 the SCLC joined other organizations in an ultimately unsuccessful legal initiative to repossess land in McIntosh County that had been taken from 70 Black families for use during World War 2 but ended up in the Harris Cervix National Wildlife Refuge instead. In the same yr, SCLC's Lowery, speaking at a rally in Macon, spurred the metropolis into initiating racial justice in hiring practices.

In 1980 a Wrightsville SCLC leader, John Martin, was arrested past the sheriff of Johnson County for refusing to go out the sheriff's office. The abort prompted protests past Black Georgians, followed by turbulence. Nine weeks of weekly demonstrations amid mounting tension ensued, and finally a biracial committee was formed to try to resolve the situation. A ceremonious suit was brought against the sheriff and a number of others; although the case was initially lost, the SCLC brought information technology before a federal appeals courtroom, where it was partially won.

Leadership Changes and the Post–Civil Rights Era

Andrew Young became SCLC's executive director in 1964. Four years after, he was named executive vice president but resigned in 1970 to run for Congress.

The assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4, 1968, thrust Abernathy into the organization'southward presidency. Abernathy could not match King'southward leadership talents, however, and schisms in the leadership and difficulty with fund-raising led to the SCLC's marked refuse in influence. In 1977, when Abernathy resigned to run for Congress, Lowery succeeded him as president. Although Lowery is credited with helping the organization regain some financial strength, numerous factors (competing civil rights organizations, the disenchantment of youth and Black militants impatient with its methods, and on the positive side, accomplishment of its original goals) contributed to its less visible profile in today'due south human justice motility. In addition, ongoing trouble inside the SCLC, including declining membership, fiscal difficulties, and political infighting, weakened the system.

Numerous changes in leadership characterized the 2 decades following Lowery'southward presidency. After Lowery'southward retirement in 1997, King'south son, Martin Luther Rex III, led the SCLC until Nov 2003, when the Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth became the acting president and chief executive officer. In August 2004 Shuttlesworth was elected president, only to resign from office three months later. The board elected Charles Steele Jr., of Tuscaloosa, Alabama, equally Shuttlesworth'due south successor in November 2004.

Steele served until 2009, when Bernice Rex, a daughter of Martin Luther Rex Jr., was elected president of the organization. King, notwithstanding, never reached an agreement with the SCLC lath regarding the terms of her presidency, and in January 2011 she appear that she would not accept the position. Howard Creecy next causeless the presidency and served in that chapters until his expiry in July 2011. Martin Luther King Jr.'due south nephew Isaac Farris succeeded Creecy but was replaced in Apr 2012 by the prominent civil rights leader C. T. Vivian, who was named interim president. Steele returned equally president in July 2012.

Although the SCLC has not forgotten its original goals, the focus has shifted to new causes, including wellness care, job-site safety, and justice in environmental and prison house organisation matters, as well as fair treatment for refugees. In 2003 in that location were seventeen Georgia chapters and affiliates of the SCLC. The organization publishes its ain magazine and continues to work for ceremonious rights and the enhancement of quality of life.

In May 2012 a collection of material documenting the SCLC's history from 1968 to 2007 opened to the public at the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library at Emory University.

Source: https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/arts-culture/southern-christian-leadership-conference-sclc/